Expanding Oz

Expanding Oz With GEnerative A.I.

Tap the Boxes to Expand or Collapse Sections

Project Brief

By combining generative-AI with vocabulary accessed from periods of art history, design, cinema, architecture, materials and the natural world, I have produced a remarkable series of images and animated sequences depicting a cinematic vision of Oz based on the fairyland and characters explored in L. Frank Baum’s children’s novel, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900).

Throughout the process, I have gained valuable insight into how generative models are trained and function, as well as experience engineering prompts across a variety of tools.

I often stack methods to further develop my ideas, either by deploying another generative model or by making use of creative software such as the products available in the Adobe Creative Suite.

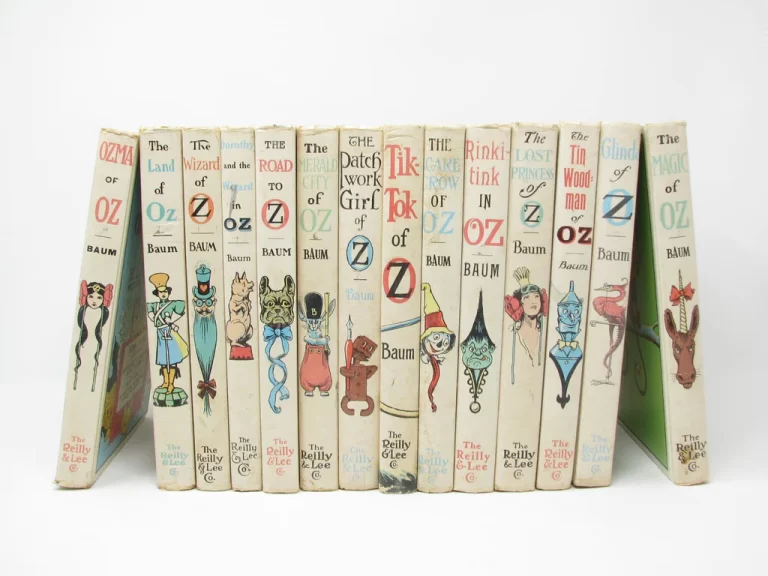

The fourteen volumes comprising L. Frank Baum’s “original fourteen” Oz novels, a series that was officially revisited by authors including Ruth Plumly Thomson and Rachel Cosgrove

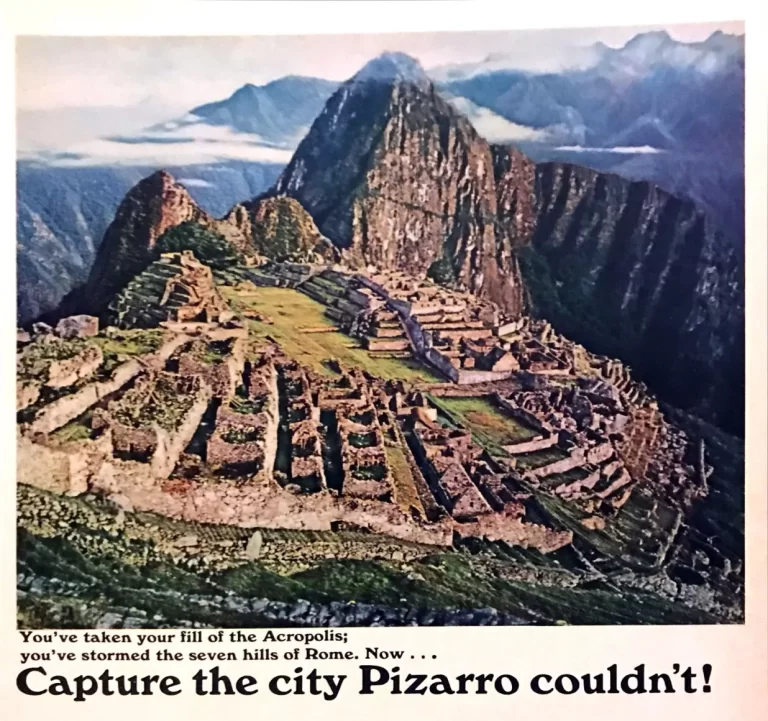

The Wonderful Wizard Of Oz (1900)

In L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, an orphaned American girl lives on a destitute farm in grey, rural Kansas with her adoptive Aunt Em and Uncle Henry. She is sent on her own version of Homer’s Odyssey to the magical fairyland of Oz by way of a tornado that sweeps across the dry Kansas plains.

Dorothy Gale’s original voyage imaginaire is marked by dangerous encounters with exotic magical beasts and bizarre, often macabre personas with tragic issues of self-perception.

Woven throughout with turn-of-the-century Americana, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is regarded as the standout archetype of modern age American fairytale folklore, much like Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Alice Through The Looking Glass are recognized as such in Great Britain.

JUMP TO SECTION

Cinematics

Animating Oz using PikaLabs

Disruptive Innovation

Generative A.I. is a highly disruptive innovation in computer science and technology that is shifting the animation and film landscape at a disorienting pace.

Solo creators and small teams are stitching together generative animations that exhibit some of the qualities of high-budget productions incorporating complex CGI.

"In The Style Of"

“In the style of” is a powerful syntax in the prompt engineer’s arsenal. Making reference to specific decades of film and genre cinema, as well as the terminology film production still evoked the desired visual flavour often within the first series of generations.

Naming specific artists, cinematographers or directors and their work, such as Stanley Kubrick and 2001: A Space Odyssey, was a similarly effective technique for achieving visual flavour in sequences and static images. That flavour is then superimposed onto the attempts by the model to accurately assess the characters and settings described in the body of the prompt, in the hopes that the model will generate the desired composition.

In addition to cinema, I often reference periods of art history and artistic movements in my prompts, using terms like Baroque, English Pastoral, French Impressionism, Expressionism, American Futurism etc. to guide the style. Using vocabulary in this way allows prompt engineers to paint in the approximate voices of Leonardo, Donatello, Raphael and Michelangelo.

Or, perhaps; Rembrandt, Gentilleschi, Magritte and O’Keefe. The possibilities and combinations exist on many orders.

Uncanny Valley

Particularly with generative animation, the audience at this point tends to be able to perceive the qualities of A.I. quite clearly.

Generative outputs are most often marked by an A.I. sheen, and an amorphous quality that becomes characteristic of the objects and characters we attempt to generate into a scene. This often evokes a disquieting sense of the uncanny valley; the representations don’t feel quite human or real.

Steering The Prompt

In generative A.I., we use the verb steer to describe the notion of leading the model towards or away from an outcome by way of the prompt; it’s a significant challenge to steer the models away from producing unwanted qualities evoking the uncanny valley.

The Chilling Effect

Despite clear deficits in precision representation common across available generative products, serious and legitimate concerns are already apparent for many creative and information sector workforces, with material impacts already being felt.

The sudden boom in availability of these tools, including LLM’s such as ChatGPT, is having an ongoing chilling effect on many creative industries as automation tools make it possible to digitally publish an unfathomably large mass of A.I. slop at warp speeds.

Platforms like Etsy, which were already proving challenging for solo artisans and craftspeople to succeed on due to the volume of drop-ship style businesses taking a large chunk of the market share, now have to contend with the challenge of moderating content for the presence of mass-produced A.I.

Solo creators are now competing against rapidly automated masses of A.I. content, which is only partially moderated through self-reporting mechanisms which have only recently appeared on various content-sharing and communication platforms.

Legislative branches of governments and institutions are currently challenged with establishing clear and consistent principles when it comes to creating legal frameworks around the sudden widespread appearance of generative tools and their implications.

Rapidfire Ideation

Generative models may offer a rapid-fire way to establish elements of tone and setting for the purposes of ideation and storyboarding; generative tools could help guide creative teams in establishing the principles behind the detailed work they intend to produce.

Art Directors could more clearly articulate an intended movement or behavioural pattern with a generated sequence; production technicians could then recreate those behaviours using tools like Cinema4D.

Generative models could potentially be useful for rapidly producing B-roll of certain elements of a scene. Generative models are fairly strong at reproducing common particle systems like smoke and fire, or animated material surfaces like water and shifting sand.

Pattern Recognition

A repeating pattern or textural quality such as tall grass swaying in the wind, waves in the middle of a vast ocean, or a starry night sky can be convincingly replicated and may even reasonably circumvent the invocaton of uncanny valley. A night sky may be styled as if it were shot on Super8mm—a filter effect that a generative model could effectively reproduce.

Just don’t expect a precise representation of the constellations in our night sky; what you will likely generate is an overall impression of that thing, represented as a pattern and lacking in contextual and mathematical accuracy.

Rubber Creatures

Consistent animated representation of complex forms is still too nuanced of a task for the available models to perform with close accuracy.

The bilateral structure of the human form as it moves through implied space, as well as our attempts to steer implied characters to perform actions and interactions within an environment are proving challenging to execute with precision; the approximate representations warp and become disfigured, even during brief sequences with relatively minimal implied movement.

Plateau Of Precision

It remains to be seen what the plateau of precision will end up being; will we be able to solve the problem of the mutating human form and its component parts?

Some have suggested that we are already nearing a plateau of precision that the current iteration of models will ultimately be capable of.

Integrated Media

The case of the deepfake is not a new global phenomenon; convincing deepfakes have been spreading since around the arrival of widely accessible key-framing software like Adobe After Effects and Final Cut Pro.

There exists at the present time a certain level of hysteria around the mass proliferation of A.I. deepfakery, and an accompanying fear that there is a narrowing gap between the physically real truth and a mathematically-generated fiction, often aiming to destabilize our sense of what is real.

Vast piles of A.I. junk and wonky deepfakes are a challenge that exists now as a direct result of this sphere of innovation. The mass spread of access to generative tools has led to a monumental surge in the amount of data being produced and published to the web in the form of text, code, images, audio and video. Unless we can come up with a clever way of precisely vacuuming the material from the web, or tagging it at inception for omission or timed-deletion, we are at risk of drowning in the storm surge of A.I.-generated content.

When it comes to generative A.I. reducing the amount of practical paying work available to animators and filmmakers, it’s my current perspective that truly convincing and integrated use of generative A.I. requires a high degree of human experience and technical finesse at all stages of studio and digital production in order for the generative models to produce artefacts worth integrating into current workflows. If generative A.I. is the inevitability, I think animators and filmmakers should lead the charge and assert agency over these tools, becoming the experts (much like when Corel and Adobe disrupted creative industries with their suites of digital tools for creatives).

Ultimately, great films are really about how the artist wields the tools rather than the presence of the tools themselves.

Images

Using Midjourney to reimagine Oz in the likenesses of enlightenment-era oil painting, early 20th century photography and 20th century cinema

Dorothy Gale: The Grass Witch

Producing an uncommon or inhuman skin tone in Midjourney was surprisingly difficult to do using text prompting alone. It required me to upload reference photos and go through a process of steering the prompt towards capturing the precise elements from each reference image that I wanted to have represented in the final composition.

Juxtaposition is a commonly deployed formal element of design. We can often spot its use in editorial illustration and graphic design. Similarly in fantasy and science fiction, we can identify moments of formal juxtaposition in many of the creative ideas, character designs and settings.

Consider the four named elements in the concept of the “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles”: four separate elements are juxtaposed on top of one another to form a new idea.

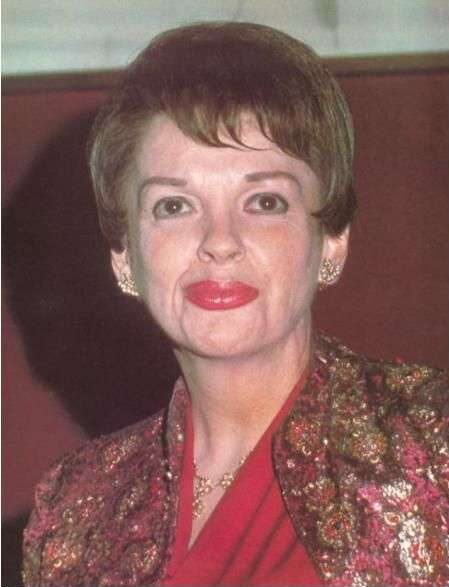

Toggle Between Inspiration/Generation

Judy Garland, age 45

A depiction of the Green Man or Green Woman; an archetype found in medieval folklore

The successful juxtaposition is followed by a process of generating variations and tweaking the prompt until a more precise or desired outcome is achieved.

Glinda: The Crystalline Buddha

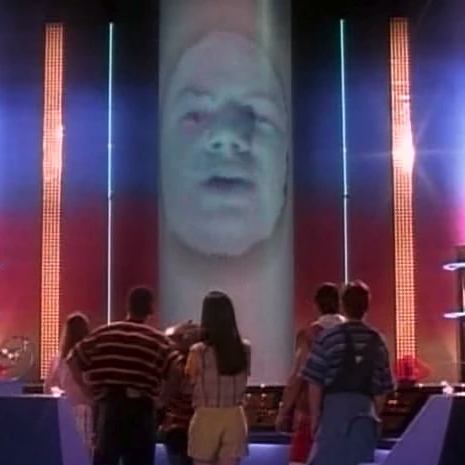

To reimagine Glinda The Good Witch, I made reference in the prompt to the character of “Zordon” from the Americanized re-release of Japan’s Super Sentai, AKA The Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers. I also made reference to 1940s-1950s Americana and Retrofuturism from the Atomic Cold War Era.

In the distant future of Oz, I imagine that Glinda no longer exists in humanoid form: she has transformed over great lengths of time into a pink crystal shard; she is tucked away on a grassy glade, surrounded by obsidian boulders jutting up from the ground around her.

Billie Burke as Glinda the Good Witch of the North, accompanied by Judy Garland as Dorothy Gale in Munchkinland in the 1939 Wizard of Oz musical

Zordon as he appears in the Power Rangers headquarters in the Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers 1990’s television series

Zordon’s corporeal form in Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers: The Movie (1995)

Unexpected Phantasmagoria

Juxtaposing the shape and movement quality of a jellyfish onto the textural quality and situational context of a cloud produced a series of phantasmagoria from some Art Basel of the future.

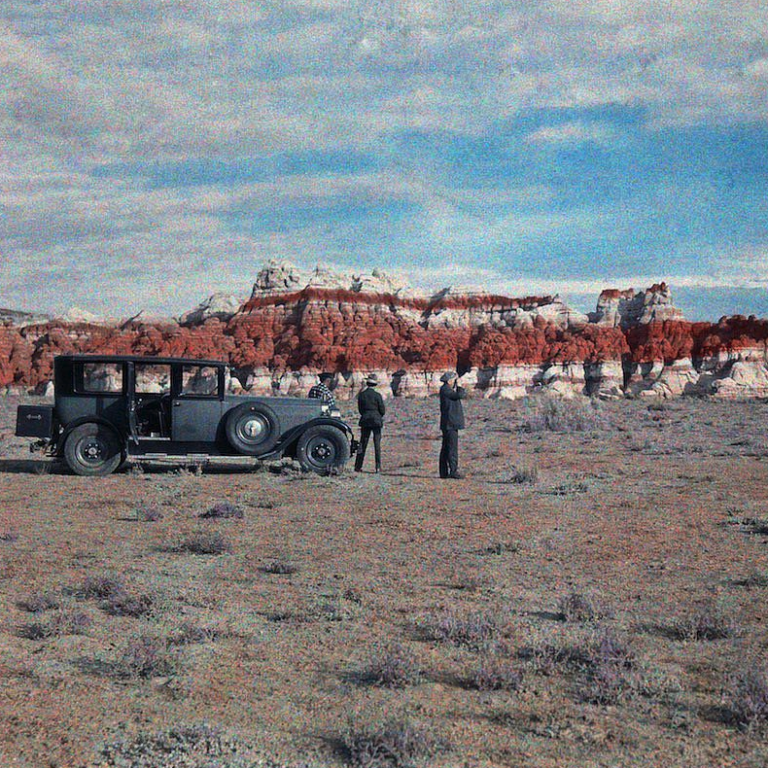

The prompts made reference to pastoral oil painting from the 18th-20th centuries, as well as early colour photographs known as autochromes to produce these alien phenomena.

In The Style Of Matthew Barney

Matthew Barney is a contemporary cinema artist who uses high-tech film cameras and cinema-grade prosthetics to build the surreal and provocative worlds of his expansive film series, Cremaster Cycle(1-5); the production of the complete work spans multiple decades.

Using the syntax “in the style of” generated representations of the humanoid Cowardly Lion from MGM’s 1939 Wizard of Oz musical with visual stylings reminiscent of Matthew Barney’s cinematography-driven artistic works.

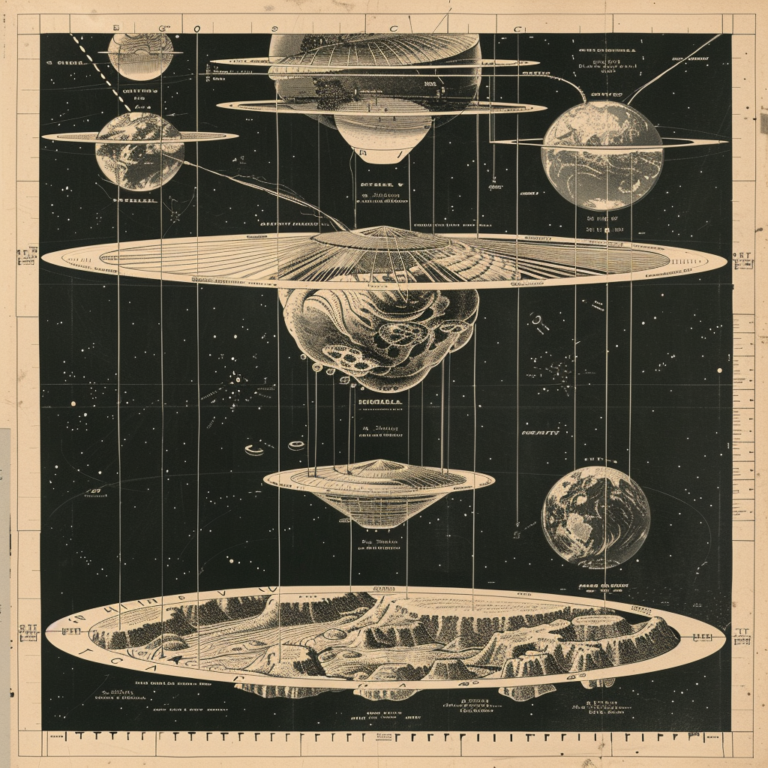

The Distant Future Of Oz

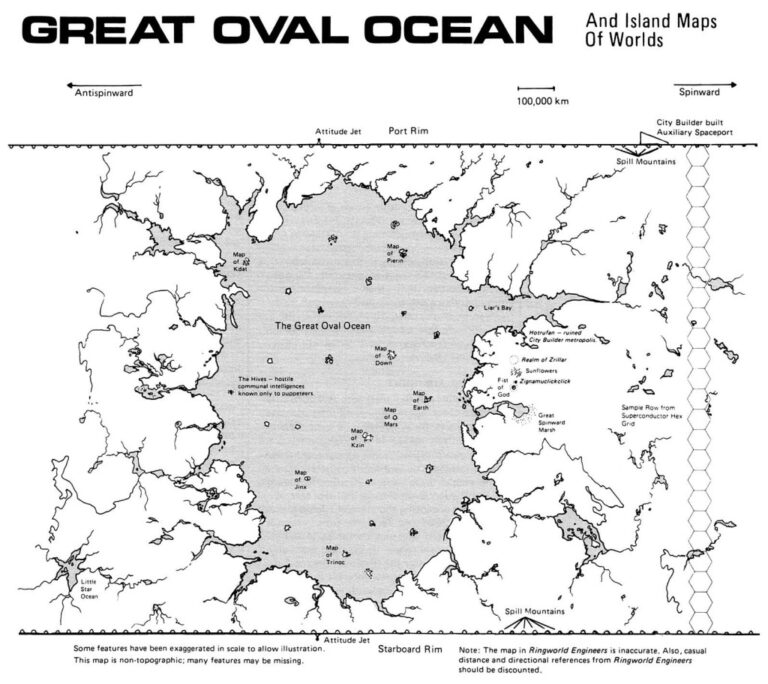

In Larry Niven’s Ringworld (1970), the small crew of a reconaissance mission in deep space find themselves crash-landed on a supermassive artifact in the shape of a ring. The ring orbits around a G-class star much like our own Sol. The structure is nearly six hundred (600) million miles in circumference, and one million miles across.

An astronaut stands at the edge of one of the “Rim Walls”, and looks across the million-mile expanse to the other side. A thousand miles below him is the surface of the Ringworld.

The inner face of the ring is occupied by millions and millions of miles of irrigable land and liquid water. In the center of the map below, you can see a tiny group of islands labeled “Earth”; this island is represented at the real scale of Earth’s landmass, illustrating the true vastness of the ring.

The map depicts about 1/600th the length of the total structure. The walls on each edge are a thousand miles high—the only thing keeping the precious layers of atmosphere from seeping out into space.

At two opposite points on the Ringworld are two vast oceans which counterbalance the weight of the ring and help keep it in orbit around it’s star.

It is megastructures like the Ringworld that have inspired my vision for the distant future of Oz. To imagine the sheer size of the Ringworld and to imagine ourselves occupying such a structure pushes our imaginations to their absolute limits, and possibly even produces a sense of the sublime.

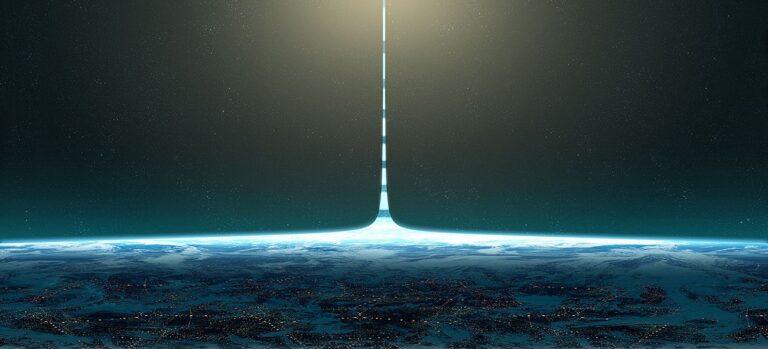

An artist depiction peers lengthwise down the ring.

A scale model of the Ringworld and how it might appear to a distant observer who is several hundreds of millions of miles away from it

In the final entry of my forthcoming trilogy, The State of Magic, a demigod-like Dorothy Gale perfects a method for slingshotting probes in-between the folds of reality, to emerge on the other side of the fold, in sister universes connected via inter-dimensional portal.

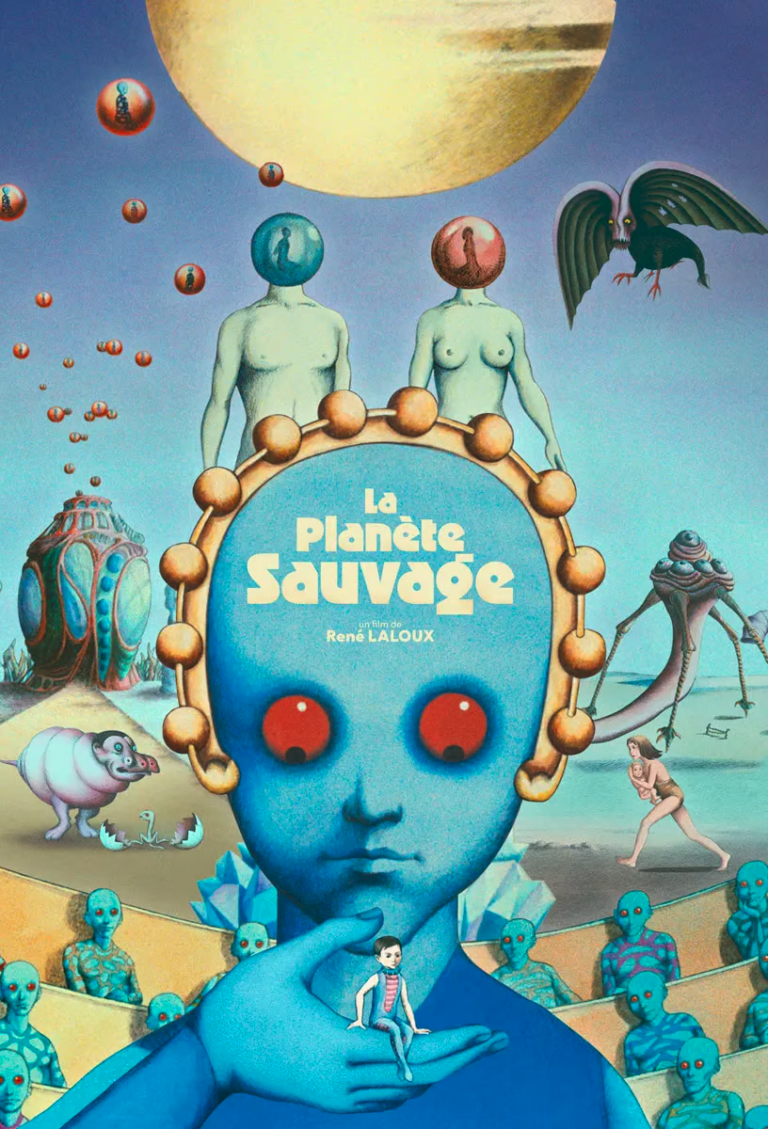

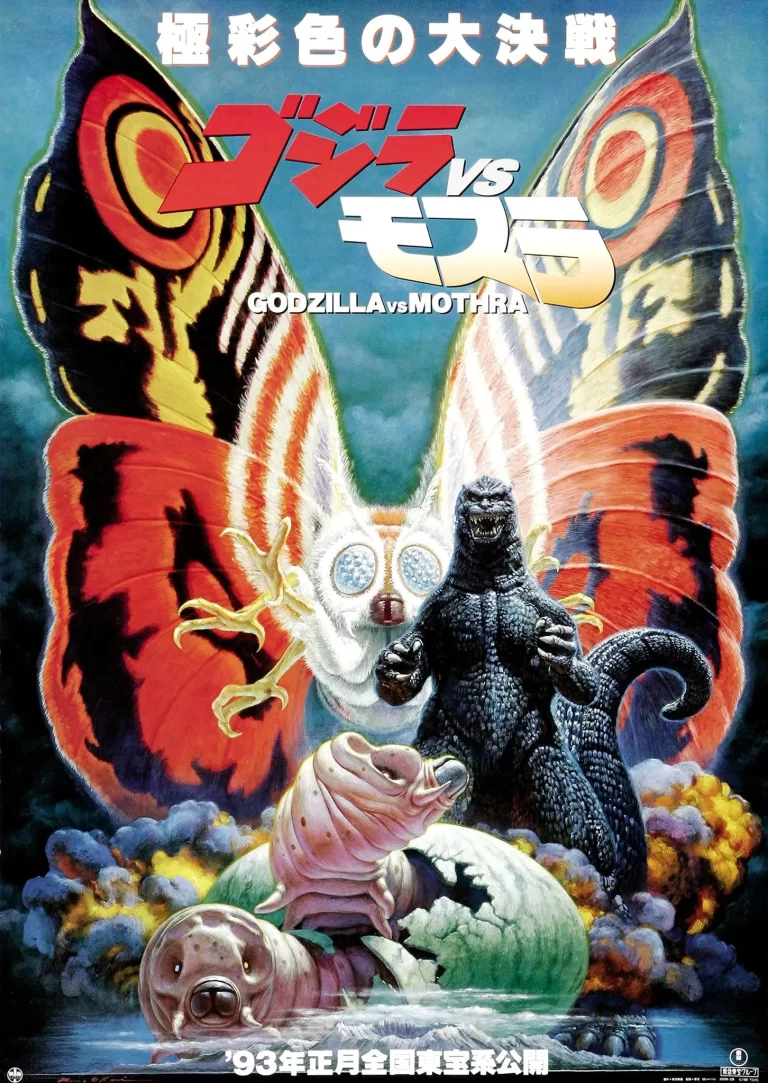

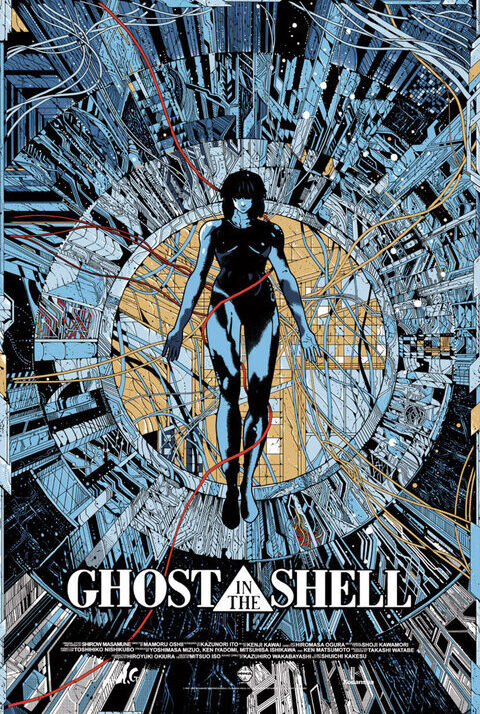

From (Top) Left: La Planète Sauvage (1973), Godzilla VS. Mothra (1992), Ghost In The Shell (1995)

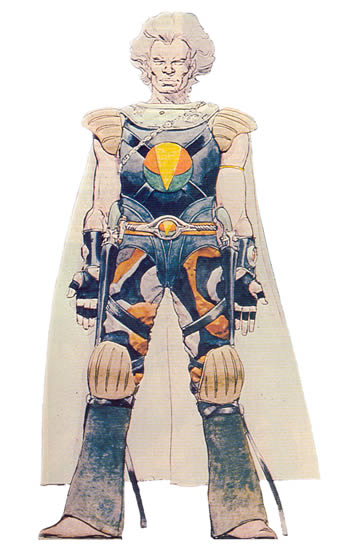

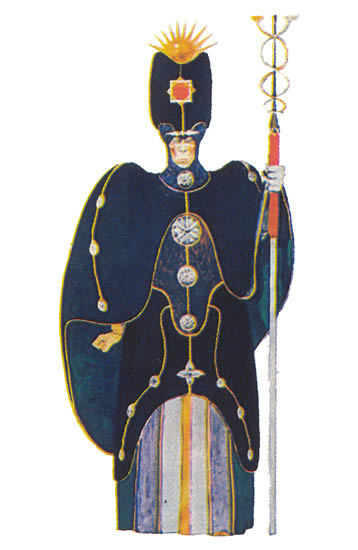

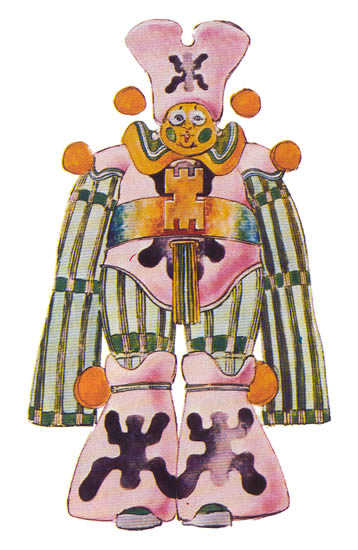

Concept art produced by Moebius/Jean Giraud for Jodorowsky’s Dune, a chronicle of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s quest to produce a live-action Dune film in the 1970s; the film sadly never made it past pre-production

Professor Gale stands in the poppyfield against the back-drop of the inter-dimensional probe, and a sister universe hovering in the sky

Professor Gale sends a Kaiju-like monster back to Earth after a threatening messenger warns her of danger awaiting her there

Professor Gale’s organic and mechanical schematics for blasting probes in-between the folds of the sister universes

A mysterious creature called “Galecrow” witnesses worlds collapsing in upon one another in the distant future of Oz.

The Yellow Stone Fortress

Inspired by the yellow brick road, ancient citadels in Middle Eastern locales such as Iran and Syria, as well as Catholic monastery gardens or “cloisters” and botanical gardens.

Arg-e-Bam Citadel, Iran

Krak des Chevaliers, Syria

The Met Cloisters, New York City, USA

Phipps Conservatory, Phittsburgh, USA

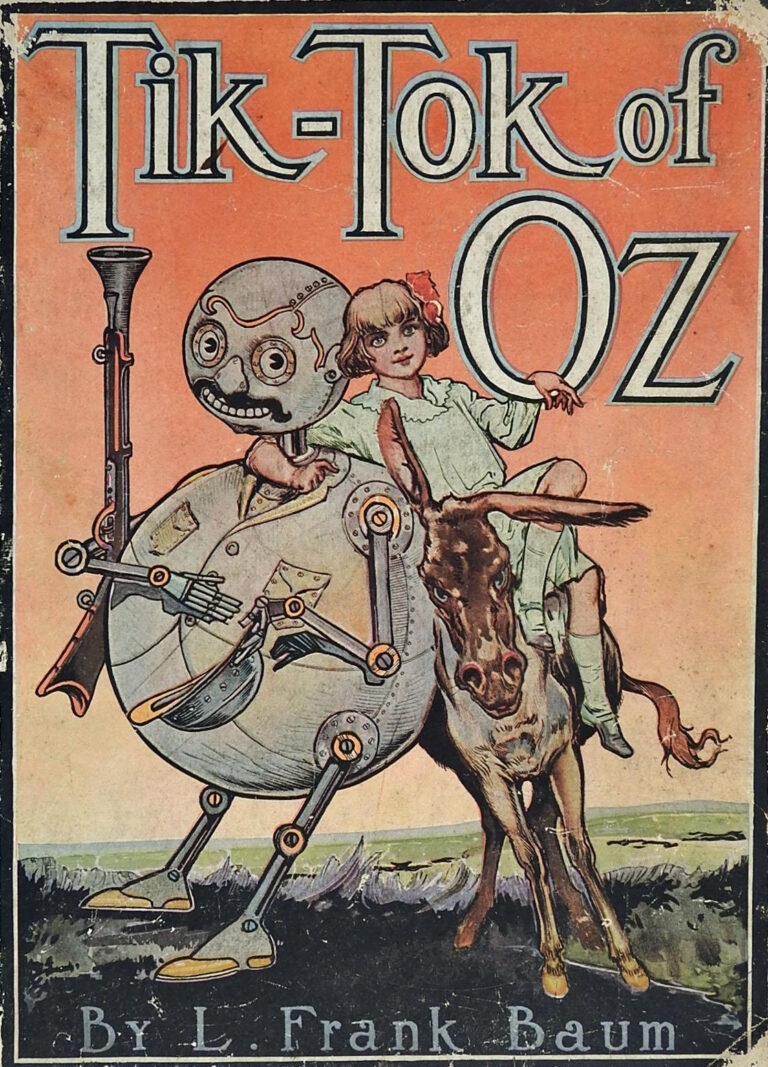

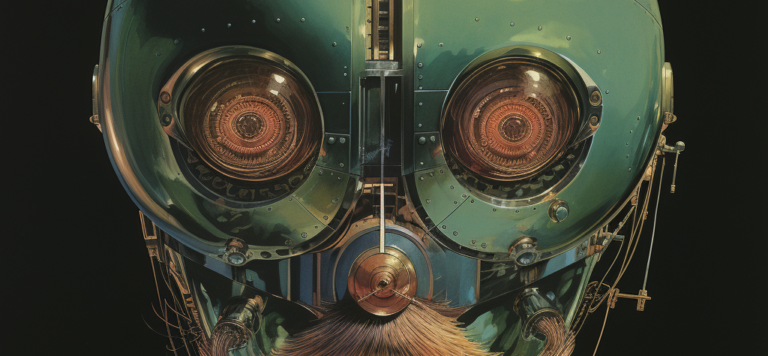

The Robots Of Oz

L. Frank Baum is occasionally credited with being one of the first of the authors in the modern western literary canon to depict the concept of a robot.

Tik-Tok, a rotund wind-up-man made of brass, hilariously shares a name with one of the most popular social media and entertainment apps on the market today.

In my derivative trilogy, Dorothy and the Monarch of Oz, Queen Ozma, both try their hand at developing the next-gen of robots of Oz.

Expanding Oz With Creative Writing

Authoring epic tales set in the Land of Oz, and voiced “in the style of” science fiction juggernauts including Alice Bradley Sheldon and Larry Niven.

The Gale Of Kansas, part I of my derivative Oz trilogy

The Fortress In The Sand, part II of my derivative Oz trilogy

The State Of Magic, part III of my derivative Oz trilogy

I am in the process of developing three sequels to L. Frank Baum’s fourteen Oz novels.

My work is heavily influenced by the work of science fiction authors including Larry Niven and Alice Bradley Sheldon. Philip Jose Farmer delivers his science fiction take on Oz in the novel, A Barnstormer In Oz.

The blog post below goes in-depth into Oz’s cultural influence on science fiction, the science fiction authors inspiring my work, as well as my process of research and writing.

Below, you’ll find summaries of each entry in my proposed trilogy accompanied by generative and found images:

The Gale of Kansas

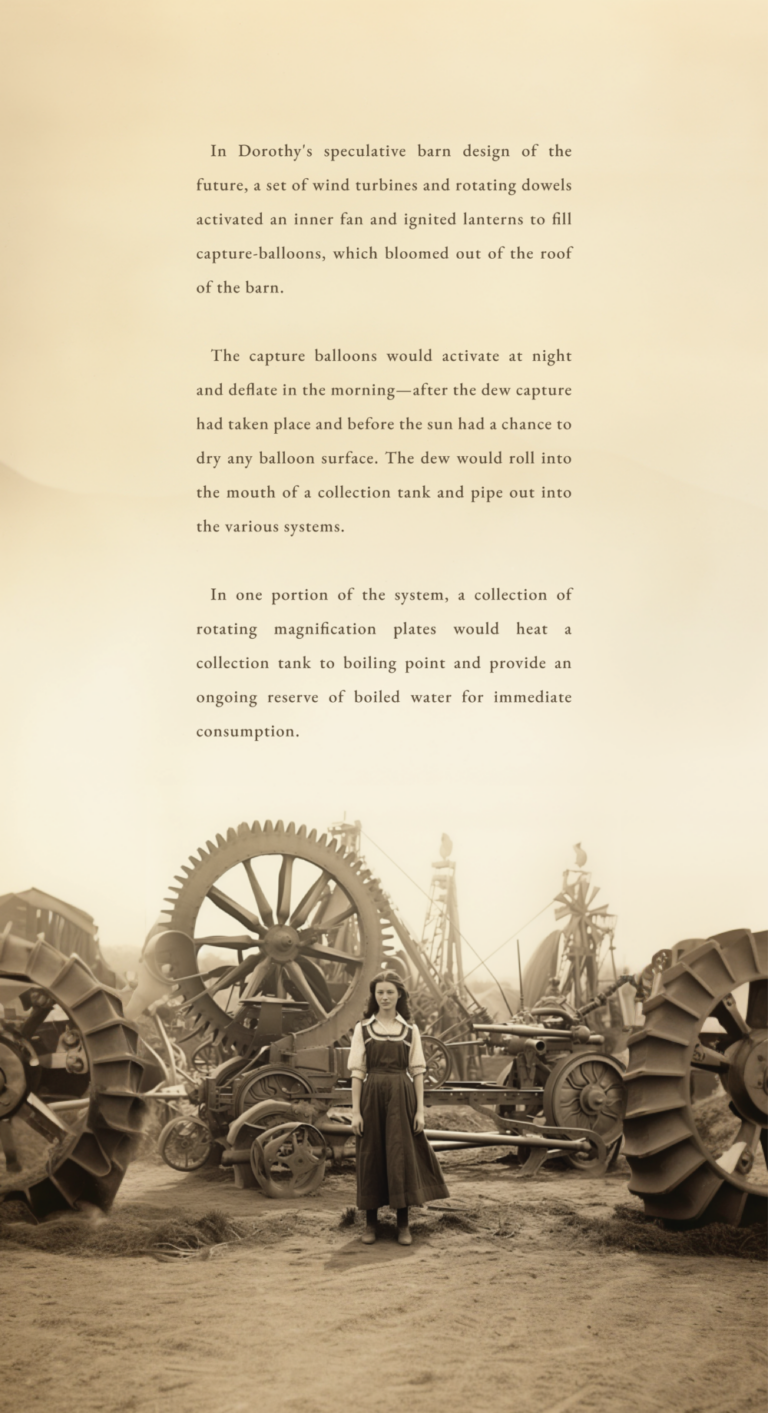

In The Gale of Kansas, Dorothy grows up to become a skilled agricultural engineer in rural Kansas. Having amassed a small fortune via the patenting of farming technology, she eventually pivots to international travel. She becomes a master of genealogy and archeology, tracking down the ancestors of the Wizard of Oz in the hopes of uncovering the secret to transporting herself back to the fairyland of her childhood dreams.

Professor Gale manages to engineer her way back to Oz in the year 1955, after spending over half of her life piecing together a machine using esoteric blueprints and ancient parts unearthed during her years spent abroad.

Upon arrival back in Oz, Dorothy is physically transformed by the medium of the wormhole that returned her there. She is immediately challenged with coming to terms with the parallel Cold War taking place in Oz between the Nome Kingdom and Queen Ozma, the monarch of Oz, who commands an army of robots from the safety of her terrifying network of portal-mirrors: The Mirrorway.

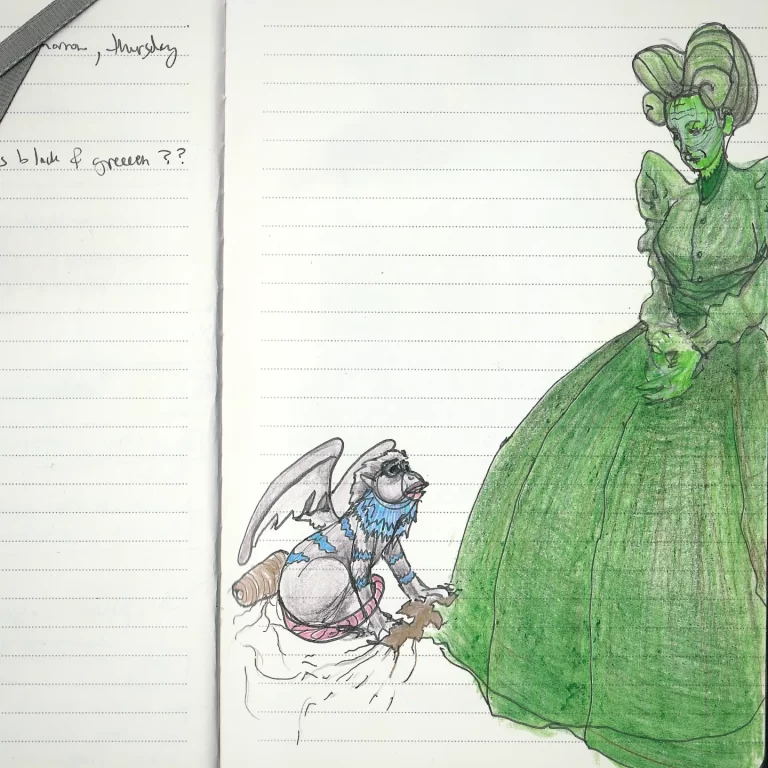

The Fortress In The Sand

In The Fortress In The Sand, Dorothy lures the feral winged monkeys into her fortress at the edge of the Deadly Desert; she masterfully sculpts them, through a series of dangerous trials-by-fire, into a cunning and resourceful cavalry of desert scouts and engineers.

Dorothy appears to the monkeys as a mad genius; they are unaware of her true origins or historical dealings with their ancestors. They observe her conducting morbid experiments, including the genetic engineering of a new species of plantimal capable of withstanding the lethal desert sand.

To what end is Dorothy conducting these experiments, and what other secrets does the mysterious baroness keep hidden away in the depths of her yellow brick fortress in the sand?

The State Of Magic

In The State of Magic, Dorothy is situated in the distant future of Oz, where she is slingshotting inter-dimensional probes back and forth between Oz and Earth.

This sets off a chain reaction of events that threatens the very existence of both worlds, and possibly even the universes in which they reside. Dorothy is visited by a series of messengers sent by terrible and unknown forces of inter-dimensional magic and science, taking her to task for her actions and decisions.

Dorothy is tasked with pioneering a new voyage imaginaire to a mysterious third world called Oobliad. There, she must seek out the answer to the problem of worlds collapsing in upon one another.

Expanding Oz With Illustration

A meditative counterpoint to the excitement and velocity of generative imagery, the published novels will include hand-drawn illustration in the spirit of John R. Neill, Oz’s resident illustrator for the majority of the series.

Thank you for visiting! I can be reached via email at

Blogs

- Deconstructing The Imposter Within [Part I] — Impostor Syndrome, Futureshock & Personal Creative Expression

- Deconstructing The Impostor Within [Part II] — Expanding Oz & Effectively: The DBT App

- Deconstructing The Impostor Within [Part III] — A Five Step Plan For Resolving Feelings Of Impostor Syndrome

- Expanding Oz: Finding Inspiration For Dorothy In The Life Of James Tiptree Jr. AKA Alice Bradley Sheldon